My Climate story is intertwined with my identities

My Climate Story begins with my ancestors crossing the Kala Pani (Black waters) Atlantic Ocean from India to British Guiana as part of the Indentured Servitude. Some came through being captured, some because they were promised lands in British Guiana, and most came without understanding the contract they had signed. My ancestors came to replace the recently freed African slaves. Labor was needed to tend to sugar plantations in the Caribbean and to feed the Europeans who had already profited from the benefits of a capitalist world and cheap labor.

My story begins here because my ancestors knew how to farm the land. My climate story begins here because my ancestors were resilient and I am fighting for my small coastal country to prepare itself and become resilient to climate change impacts. My climate story begins here because the injustice of climate change has the worst impacts faced by those who contributed the least to the problem. My story begins here as I think about my sisters and brothers in the Small Island and Development States (SIDS) who are already suffering from climate disasters.

Up until this point, my life was split between growing up in Guyana and spending my late teens and early adulthood in the United States. Two vastly different environments, but both showed clearly the impacts of climate change and environmental injustices. I have seen floods swallow up my tiny city, Georgetown, in 2005. Rates of death from asthma in the Bronx are about three times higher than the national average. Hospitalization rates are about five times higher. This can be directly attributed to pollution. In 2012, I saw that even megacities like New York can be crippled by hurricanes like Sandy.

For most of my life, I had no other choice but to get involved in ways to make our planet a more liveable and sustainable place, while prioritizing justice. In every generation, there is a cause to fight against. As someone interested in social justice, I see the connection between climate change on all issues related to justice. Rejecting and rising against the current state of the Earth is the fight of my generation and it is the most important fight we have ever fought. This is not an easy fight, and we live in a time where climate change is still being debated by our leaders, even though those affected continue to cry out for changes in our system.

Patriarchy, colonialism, racism, and classism are a part of my story. I believe that these are systems that need to be dismantled for us to achieve a just and sustainable world. In my role as a climate advocate, I want to center the voices of those most vulnerable in particular women, youths, and people of color. Speaking from my experience, women face significant challenges that make it impossible for them to participate fully in the discussion that impacts their livelihoods. When climate disasters strike they are the most vulnerable, in Guyana one in every two women experience intimate partner violence. The challenge is complex, it is one that is based on the survival of women and the survival of the planet.

The world is crippled by COVID-19, which can be seen as a direct call to repair the relationship with the natural world and to build back better. It is time to build back in a way that is just and equitable for those most vulnerable. Climate change and COVID-19 are justice issues. 2020, a new decade, the beginning of all things new, must serve as a wake-up call for systems change, for radical change in the way our society operates.

My generation is the last to act on climate change. My generation is also witnessing the effects of climate change impacts. I care about this issue because I know that within my lifetime, these events will worsen. This is an issue that brings anxiety to those younger than me.

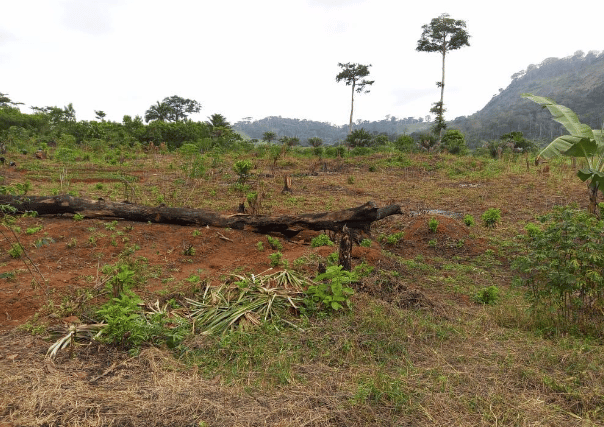

When my ancestors were brought to British Guiana, they worked the land for the benefit of the colonizers. What would they say if they knew that those same crops (sugar and rice) are now being threatened by the climate change impacts such as flooding, saltwater intrusion, and increased pests? I was born into this land and fell in love with it, but this land is vulnerable to climate change impacts such as sea-level rise, flooding, heatwaves, air pollution, storm surge, droughts, and deforestation.

My ancestors were resilient, and so I believe I can be resilient too. There is much despair and loss but there is also hope, compassion, and revolutionary love that comes from everyday citizens who are committed to making the planet a better and more equitable place. This is my climate story, a story that started with my ancestors, a story that I hope has a positive ending for the generations that come after me.