COVID-19 has changed the world we are living in today, but we must not forget other pressing issues facing our planet. Though economies have slowed, the heating of our planet has not. Climate change is two small words representing a radical transformation of our planet, billions of data points, millions of climate scientists and campaigners, and a limitless number of stories from around the world. Climate change is more than an environmental issue; it is a global social problem bound by multiple human security issues.

The tales my Nana (mother) used to tell us about her lovely island are still quite clear in my mind. Every night, as the light from the kerosene lamps shot golden ambers across the wall, we would cuddle together and hear about Nana's voyage over the vast ocean and whatever misadventures they had. We were all enthralled and vowed to go someday as a result.

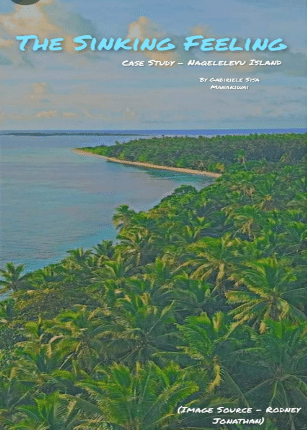

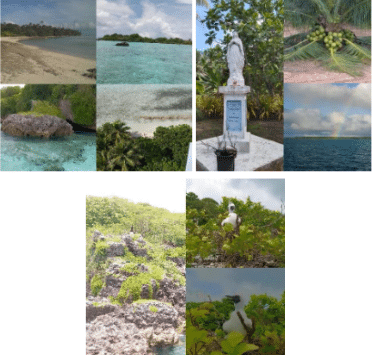

Around 40 years ago, my Mom finally departed from her island. Owing to its geographic location, the island only has one village. Hence there is neither a school nor a church for kids on Sundays. Given that her island is also home to rare, exotic birds that some people believe to be extinct, she frequently refers to it as Paradise. She says the people live from the sea and what tiny land they have. Her description says it all; reef fish live among the coral in crystal blue waters; turtles graze seagrass beds; tangled mangrove roots shelter tiny fish and crabs; coconut trees fringe white sandy beaches; and, in the skies, tropical birds soar. Also, the white sand beach harms their eyes when the sun beams on it. This paradise-like island, also known as "Naqelelevu Island," is a haven for birds. 37 years after leaving, Nana came back to her island, and here is her tale

To ensure the education of our future generations, our folks departed the island. We would travel back during each school break, using the stars and the wind for guidance. Traveling there would take at least a week because it is one of Fiji's most remote islands. Notwithstanding the many difficulties our people experienced, our island provided for us on land and water. Food was available, but the island had no water source, so water had to be judiciously rationed. We spent our days searching for food and the indigenous "Ugavule," or coconut crab (Birgus latro). At night, we would tell stories by a lamp. Such was island life—perfect and highly carefree. At the extreme north of the Fiji Group, or to the northeast of Vanua Levu, is the island of Naqelelevu. The majority of the island's vegetation is limestone. The region is completely flat and devoid of mountains. A bordering reef extending around 20 miles offshore protects the island from tsunamis.

In 2019, Nana went back to her island. She said this when she returned: “Nothing is as I expected". The whole island looks different. Understandably, it has been over three decades since she's been to her island. All-natural landscapes have changed dramatically if not gone. One of the main points she has brought up is that Climate change has destroyed the VANUA - loosely defined as a community. As a result, it led to the local extinction of natural resources that they rely on as sources of food, income, knowledge, cultural practices, and maintenance of the Vanua. The shoreline has retreated so far that seeing the shore is impossible. Nana learned after asking that storms, such as Cyclone Amy in 2003, Cyclone Thomas in 2009, and Cyclone Winston in 2016, were primarily responsible for the retreating shoreline. These cyclones' effects resulted in irreparable damage and destroyed entire landscapes. The expansive sandy beach has substantially shrunk, and the jagged granite cliffs that protruded into the water have vanished. There is no longer a coral reef under the lagoons. Nana claims that even the water supply is running out. Their idyllic world is gradually vanishing before their very eyes. The island is in danger of disappearing, even though fish and other marine life are still abundant and birds are still numerous.

Despite climate change's social, economic, and health implications, the people are weaving indigenous practices with contemporary methods to help them restore and recover some of the resources and traditions they have lost. One of the methods she identified was the “Solesolevaki”; this is where the people work together to plant local trees that have become extinct – to sustain them. She has also strongly emphasized that climate change be taught where people congregate, especially in churches and the Vanua community. This will enable people to be prepared for future changes instead of people running around when disasters occur.

Although the changes in Fiji are not as extreme as in other areas, they nonetheless exist. The retreating shoreline demonstrates the island's deterioration and the effects of climate change. Although some NGOs are working hard to promote conservation, it is still unclear whether climate change's effects can be mitigated or effectively adapted for a climate-resilient community. The trip home for Nana was bittersweet. She thinks back on all the days she spent on the beaches with her family, who has now passed away, but the thought incredibly saddens her that the next generation will not get to visit the island. She has come full circle, 37 years later, with 12 children and 30 grandchildren; Nana is back in her paradise or what is left.

Considering the environmental crisis, there is no time to delay for the world and the Pacific Region. Tackling the threats is everyone's business. No one sector can do this alone. It requires collective actions in solidarity. We must accelerate efforts to protect nature, invest in water and sanitation, promote healthy food systems, transition to renewable energy, and build livable islands. WE MUST BUILD BACK GREENER and listen to the marginalized community's voice in addressing loss and damage.