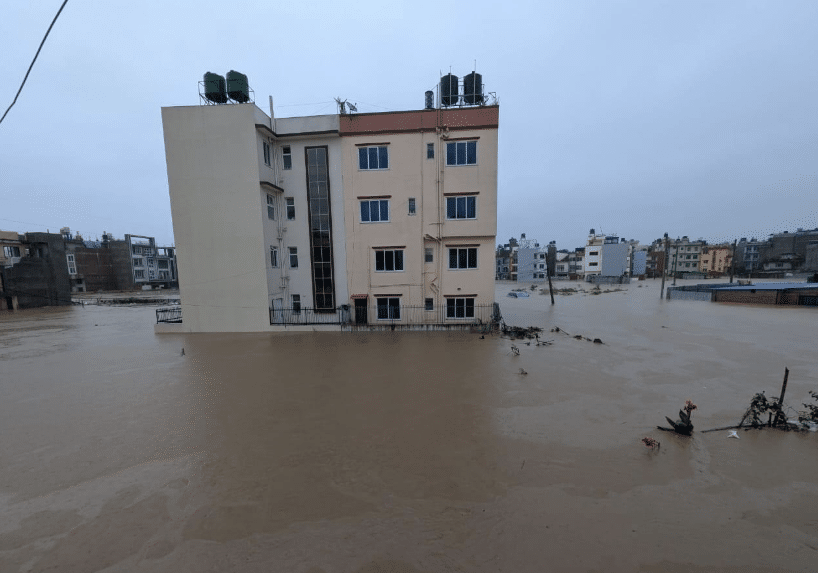

Nepal is a least developed landlocked country with the most active mountain ranges and rugged terrain. Over the past years, slow-onset disasters, such as drought, glacial retreat and infectious disease outbreaks, have been prominent in the region. Similarly, there has been an increased frequency of extreme weather events, like the tornado in the Bara-Parsa district in 2019, the Melamchi flood disaster 2021, increased wildfire in spring of 2021-2023 induced by prolonged drought, the highest temperature recorded in Damauli Nawalparasi 43.8 degree Celsius in 2024, the Dodhara Chandani flood with heaviest rainfall of 624mm in monsoon of 2024, the September 27-29 flood in Kathmandu 2024, the extreme heat waves and cold spells in the Terai region during summer and winters, the decreased water table in the Inner Terai and Chure and the glacier lake outburst and debris flow in the village of Thame in the Everest region. Flooding in the past occurred mostly in the plains (Terai), but the rapid melting of glaciers has resulted in the formation of glacial lakes, which burst during heavy rainfall and trigger debris and mudflow in the mountains. Cascading hazards are frequent occurrences amplifying the overall damage leading to greater vulnerability. In September 2024, central and eastern Nepal were hit by a catastrophic flood and landslide, causing loss and damages of approximately 50 million USD, and 224 human lives were lost. In the same flood and landslide 32 children lost their lives and 54 schools were destroyed. Rapid attribution analysis by the World Weather Attribution Group concluded that climate change made downpours behind the Nepal flood 10% intense

A resident near the flooded Godawari river shared, “This year our home was flooded twice, in June the water level reached the courtyard, but the whole first floor was submerged in the September floods, I woke up at 12 PM, it was raining incessantly, and I could eerily hear the roaring Godawari river when I lighted the phone flashlight to look through the balcony I was in the middle of the flood, we evacuated the residents of the first floor, we were praying for the night to be over. Our home was built as per the housing standards, we are more than 20 meters away from the river, I have invested so much in this house, but now nobody will buy it, the value has decreased” Another resident of a squatter settlement near Balkhu river shared her experience of flood, “I do not want to remember that day, after early warning from local administration we moved to high ground. My children's uniform and books, blankets, mattress and kitchenware were spoiled by the flood. My mind was in chaos, a guy was swept away from his home and we found his body under the bridge in the morning. We were hungry, cold and in pain.” Climate change in Nepal disproportionately impacts indigenous communities, urban and rural poor, farmers and pastoralists, women and children, people with disability and other vulnerable groups. According to the Ministry of Forest and Environment in Nepal, climate-induced disasters caused 65% of all disasters related to annual deaths in Nepal. It is also estimated that Nepal faces losing 2.2% of its annual GDP due to climate change-related disasters.

As per the World Bank, Nepal contributes 0.01% to total global greenhouse emissions. Even though its contribution to climate change is negligible, Nepal is most impacted by the adverse impacts of climate change and least prepared to address the climate crisis. With increased temperature, vector-borne diseases such as malaria, Japanese encephalitis and dengue fever, which 30 years back were unheard of in the higher altitude of Nepal, are infecting thousands of people and inflicting a public health burden. Dengue outbreaks used to happen during the post-monsoon. However, outbreak nowadays is observed in pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-monsoon in Nepal.

Another sector that is worst impacted by climate change is the agriculture sector. About 66% of Nepali people are engaged in agriculture and are small landholder farmers. Farming in Nepal depends on the monsoon, and the whole crop calendar is compromised if the monsoon is late. As crop production decreases, the food security and livelihood of the farmers are impacted the worst. Farmers of Dolakha, a district in Nepal, share that even though one has to toil day and night for farming, the produce is not able to sustain their livelihood, therefore, youth nowadays opt for foreign employment, and now the lands in villages are barren. Pastoralists in the mountains are facing the challenge of finding fodder for their herd, forcing them to move at higher altitudes. The farmers share that they can no longer predict their environment; the monsoon is erratic, droughts are prevalent, infestation and invasive species are destroying crops, and it’s difficult to sustain their livelihood as farmers.

In Nepali, there is a saying, “To drink poison one has no hand in concocting”, which aptly summarizes the Nepali climate change context. Our environment is poisoned, we cannot afford zero growth, existing inequalities have compounded, and the irony is that historical emitters lack accountability. The poor, with limited resources, are unable to adapt to climate change. For instance, when the temperature rises in summer, street hawkers, farmers and construction workers must toil in the scorching sun, vulnerable to heatstroke, but the elite can afford cooling. When a climate crisis manifests as disease, natural hazard, or disposition in the doorway of vulnerable people, climate change shifts from being a global issue to individual issues that must be dealt with on a personal level.Globally, lower-income countries have a relative loss of 75% due to climate change, despite contributing only 2% to global carbon emissions, whereas the top 10% of rich countries will only bear 3% climate-induced losses, however, contributing 48% of carbon emissions.

As of 2024, Nepal allocated 32.5% of the total national budget to highly and moderately relevant climate change activities, about 11% of the source of the total budget is external debt. The public debt equals 43.69% of the GDP, and the principal interest payment accounts for 21% of the budget, surpassing the budget for development projects. Nepal's exposure to climate change impacts, such as disasters, loss of livelihood, public health, etc., is further straining government resources and limiting the government to spend on developmental projects, thus trapping the nation in the vicious cycle of poverty. As rich nations evade their responsibilities of addressing climate change through climate finance, climate change is hitting home for socio-economically disadvantaged individuals in the form of health risks, food insecurity, water poverty, displacement, and loss of livelihood. In the climate discourse, another kind of injustice is the issue of debt. Institutions such as the World Bank and IMF display inconsistency by pledging solidarity for climate justice but offer climate finance as debt to developing nations in higher interest. In September 2021, Nepal was granted a loan of US dollar 100 million for a green, climate-resilient and inclusive development (GRID project) by the World Bank, for which Nepal is eligible for grants. Rather than investing in sectors such as education or health, Nepal should pay its debt and also address climate change.

As a citizen and youth from the world’s fourth climate-vulnerable country, Nepal, I advocate for climate debt cancellation and the end of kafkaesque bureaucracy pervading in global climate finance negotiations. Historical emitters need to pay their due with accountability and transparency, then, only climate justice will be served.